LITTLE MAC

America's First Great Marathoner

At midday on April 19, 1897, 15 runners stood on a line drawn across a dirt road in Ashland, Mass., awaiting the start of the first Boston Marathon. The temperature hovered around 60 degrees and a stiff wind blew at their backs. The men wore the colors of athletic clubs from New York to Boston. Thin leather shoes offered little protection from the dusty, rutted streets ahead. Few of them knew the challenges that this 25-mile run would hold.

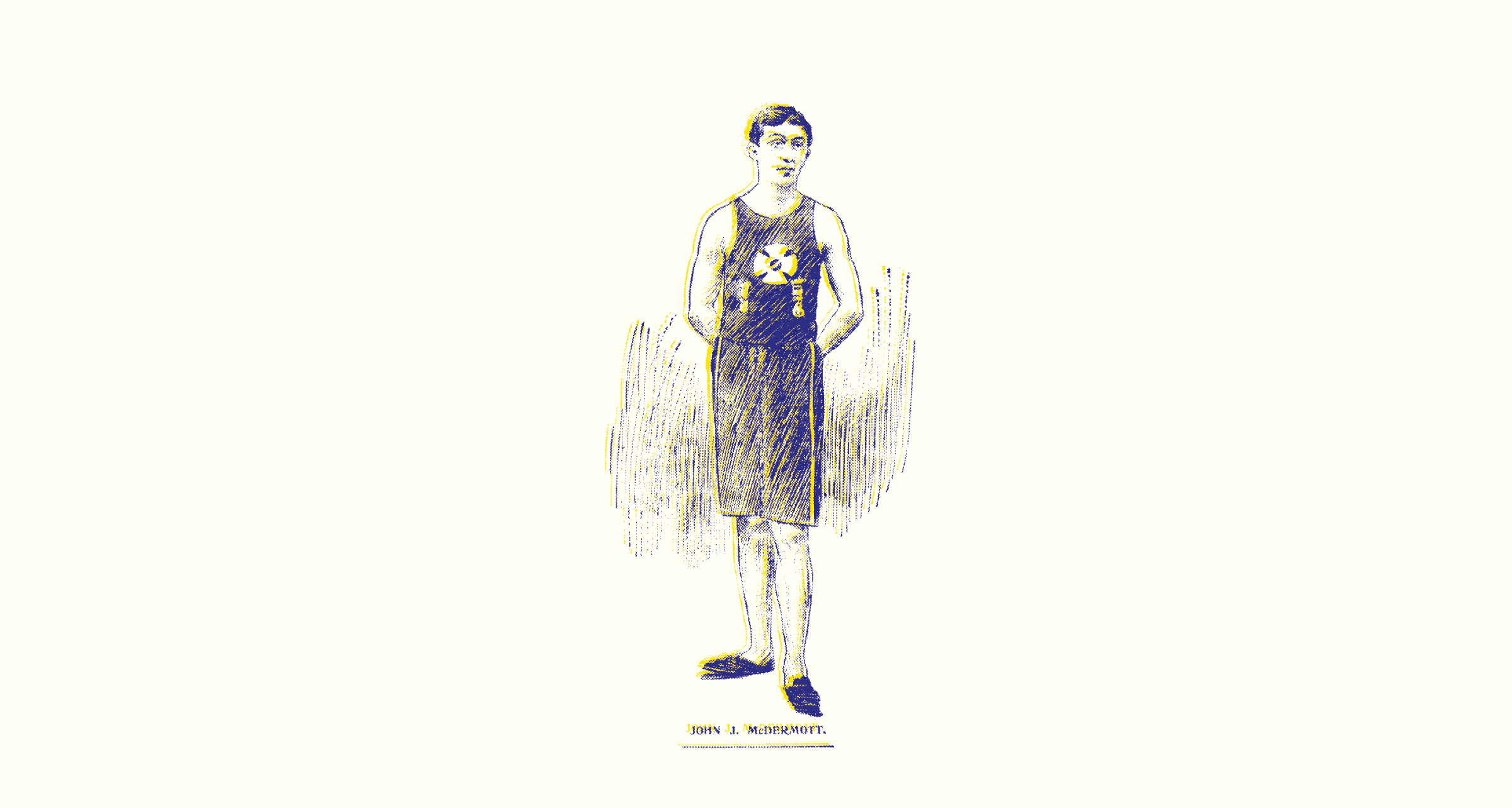

The Boston Athletic Association’s (B.A.A.) Tom Burke called out each entrant’s name. Hamilton Gray, representing the St. George Athletic Club of New York, had won a national 10-mile championship. In Harvard’s crimson was medical student and star miler Richard Grant, the local favorite. And wearing the dark blue singlet and baggy shorts of New York’s Pastime Athletic Club was 22-year-old John J. McDermott, the lone marathon champion in the field.

No U.S. athlete managed to finish the first marathon, at the Athens Olympics in April 1896. Greece’s Spiridon Louis won that race in 2:58:50, inspiring American clubs to find someone who could compete at this exciting new distance. The first North American marathon was a hastily organized event put on by New York’s Knickerbocker Athletic Club that September. McDermott, the eldest son of an Irish-immigrant bartender, James, and his wife Elisabeth, from Hell’s Kitchen, emerged as an unlikely winner.

New York City, 1896

“The competitions at Athens showed plainly that the Greeks are our superiors at this distance,” the Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote in advance of the Knickerbocker A.C. marathon. The race’s grueling course didn’t help change that perception. It stretched 25 hilly miles from Stamford, Conn., to a track near Van Cortlandt Park in the upper Bronx. Eighteen men finished the race but muddy roads and unrelenting hills prevented any from approaching the Greek’s record.

The race was marred for other reasons as well. D.C. Hall of Boston’s Peninsula Athletic Association alleged that his bicycle escort had poisoned him with a wafer. Hall led the race through 12 miles, but collapsed soon after eating the snack. According to the Boston Post, “It is intimated by several well-known sporting men of Boston that the drug was the work of some New York athlete who did not want to see Hall win.” A half-decade before the first Red Sox–Yankees game, the two cities already had a heated rivalry.

While Hall recovered in a New Rochelle pharmacy, McDermott took the lead and Hamilton Gray gave chase. The two struggled toward the Bronx, alternately running and walking. Gray got within 200 yards but couldn’t close that final gap.

McDermott fought his way up the last, precipitous hill and passed through a gate into the stadium. A large crowd, gathered for a track meet as well as the marathon finish, greeted him with a roar. McDermott, “a little lank fellow” according to one account, circled the cinder track and waved to the fans.

After finishing in 3:25:55, he grabbed ahold of two friends. One asked how he felt, and McDermott grinned. “I guess I’ll run back again,” he said. “There is no sarcasm in the Pastime Club like that of young Mr. McDermott’s,” the New York Herald reported.

Though the winning time fell well short of the Olympic record, the Knickerbocker marathon had captured the public’s attention. The New York Times devoted much of a page to the race, and many other papers gave their headlines to the marathon even though world records were set at the day’s track meet in the 600 yards, 440-yard hurdles, and discus. Boston’s stage was set.

Boston, 1897

“McDermott and Gray looked as if they had trained carefully for this race,” the Boston Post observed in Ashland. “Others of the runners looked as if they could spare a few pounds.” Grant, the miler, ran against his coach’s advice. In fact, he entered on race morning, too late to receive a bicycle escort like the other runners.

A few minutes after noon, the B.A.A.’s Burke yelled “Go!” and the runners charged toward Boston. Several fell behind almost immediately, while the others began to string out along the road as they settled into their pace. The bicycle attendants, members of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, fell in line alongside. They carried water, lemons, and damp handkerchiefs for their athletes.

Grant and Gray ran aggressively, sharing the lead while McDermott held back. They passed through Natick a quarter-mile ahead, but McDermott began to gain on them. He caught the leaders before they’d left Wellesley. Gray, who had lost to McDermott in New York just months earlier, slowed to a walk.

The marathoner and the miler battled down to Newton Lower Falls. Then the road began its unforgiving climb into Newton and the unprepared Grant stopped, exhausted, with blistered feet. He flagged down a water cart, lay in the road beneath it, and asked the driver to give him a soaking shower. “[He] is the hardest man I ever beat,” McDermott said later.” Grant tried briefly to run again but McDermott was out of sight and, with 10 miles remaining, the Harvard man quit.

McDermott, bearing the Brazilian cross emblem of the blue-collar Pastime A.C on his chest, extended his lead to nearly a mile in the Newton hills. Members of the cycling corps struggled to keep the road clear around him while hoards of spectators followed by wagon and bicycle. The Boston Herald captured the scene: “The front of the cycle cavalcade [formed] an immense crescent that looked like a great plow or scraper scooping McDermott along.”

McDermott seemed loose on the hills, laughing at the cyclists who struggled to keep pace with him. Then, showing the first hint of fatigue, he asked his bike escort to tell him when they reached 20 miles. There he stopped so the escorts could rub his legs. He took a swig of brandy and walked past Evergreen Cemetery before starting to run again. Then his left leg cramped. “Rub!” he begged. The militiamen tried to knead the cramps away. McDermott nearly became the first victim of the Boston Marathon’s “haunted mile.”

Ignoring his rebelling muscles and throbbing feet, McDermott summoned his remaining energy and began running. The crowd’s cheers grew as he neared downtown Boston. He charged through a funeral procession as it passed along Massachusetts Avenue. He ran up Commonwealth Avenue and swung onto Exeter Street. People screamed from housetops as he ran across Huntington Avenue.

The scene at the finish was reminiscent of the previous fall’s Knickerbocker event. At least 2,000 spectators packed Boston’s Irvington Oval, watching a track meet while awaiting the marathoners. The 1-mile had just ended in a thrilling dead-heat when word spread that the marathon winner was approaching. Minutes later, the slight McDermott entered the stadium. He ran a lap of the track accompanied by a mob of excited fans and crossed the line in 2:55:10. He had lost 9 pounds during the race and weighed just 114 at the finish.

Finally, an American had bested Spiridon Louis. The Boston Post’s headline the next morning would read, “BEAT THE GREEKS.” The raucous crowd lifted McDermott in the air before he could escape to the nearby B.A.A. clubhouse to recover. “My toes are blistered and the skin has peeled from the bottom of my feet,” McDermott told the press. “This will probably be my last long race …. Do you blame me?”

Boston, 1898

The Knickerbocker A.C. didn’t host a marathon in 1897. McDermott probably wasn’t too disappointed. In addition to declaring that he wouldn’t run another marathon, he’d expressed a clear preference for the B.A.A.’s event. “It is a great deal better than the New York course…. In fact, everything connected with this race was managed a good deal better,” he’d said.

In early April, McDermott placed 38th in the U.S. amateur cross country championship. A few days later, the Boston Daily Globe reported that he’d just completed a 15 mile training run in 95 minutes. At some point he had begun to reconsider his vow from the previous April. McDermott showed up for the second Boston Marathon as a clear favorite to win.

After succeeding with patience in his previous two marathons McDermott ran with a new aggression in 1898. Two Pastime teammates joined him at the front and they led through Framingham and into Natick. But the trio ultimately faded as Ronald J. McDonald of Cambridge and McDermott’s old rival, Hamilton Gray, surged by. That pair dueled all the way to Boston before McDonald pulled away to win in a surprising record of 2:42:00.

McDermott finished fourth, a minute faster than the year before. He had now run three marathons, each quicker than the last, and was just 23 years old. But despite all that promise, he had already reached his peak. Boston 1898 would be his last marathon. He then all but disappeared from the public record.

Boston, 2018

Most details of McDermott’s life were lost until this past decade. A scattered group of researchers—distant ancestors, running historians, a genealogist—found each other online and began comparing notes. They shared newspaper clippings, census documents, grainy images, and other historical hints. The biggest clue was the silver shield presented to McDermott for winning the Knickerbocker Marathon. Passed down through generations without explanation, the presence of that heirloom helped a group of sisters determine that John was the brother of their great grandfather, James Edward McDermott. America’s first great marathoner was their great grand uncle.

A number of mysteries still remain. Did McDermott marry? When and where did he die? And where was he buried? We know he didn’t return to Boston in 1899, perhaps a delayed fulfillment of his promise to retire from long distances. Over the next two years he appeared on the entry list for one cross country race and in the results for another. And then he vanished. Four years pass with no record of the champion.

His reappearance is a somber one. A Louisville Courier Journal preview of the 1905 Boston Marathon noted that McDermott had died. A year later, the Star-Gazette in Elmira, N.Y., wrote, “‘Little Mac’” was not a very strong youth at his best, being unusually frail and light,” and adding that he had died of consumption, a common name for tuberculosis—a disease that killed more than 6,000 New Yorkers per year. McDermott likely died just as officials had begun to understand that simple public health measures could prevent its spread. In 1921, Lawrence Sweeney, a Boston Globe writer who had witnessed every edition of the Boston Marathon, added one final and remarkable detail to the story: When McDermott won the first race in 1897, he had already contracted the lung condition.

To this day, details of McDermott’s life outside his three marathons remain scant. And yet, what remains is triumphant: “McDermott Won It,” The New York Herald proclaimed in 1896. Could any runner dream of a better epitaph?

Words by Marc Chalufour